I Love What Miriam Klein Stahl Is Doing

"Every day I'm lighting a candle and just hoping that a real ceasefire will happen."

Welcome to I Love What You’re Doing, and the final conversation that I’m going to share in 2023. It’s been an honor to share these sporadic dispatches with you over the course of this year, and I look forward to continuing to do so as we slip into another 365-day cycle of this thing we call time.

In my last dispatch I shared a conversation with Dr. Kate Slater, an antiracist educator and activist who was running for school board in her small-ish Massachusetts town. Update: SHE FUCKIN’ WON! Hell yes! I hope to check back in with her next year to see how it’s all going. Congrats to you, Dr. Kate Slater!

Today I offer you this conversation with my very dear friend, collaborator, and creative partner, Miriam Klein Stahl (we created these books together. Radical lil NYT bestsellers! NBD!) Miriam is an artist and educator and activist and punk and an anti-facist antiracist big ol’ butch dyke and, without a doubt, one of the wisest, most impactful people I know.

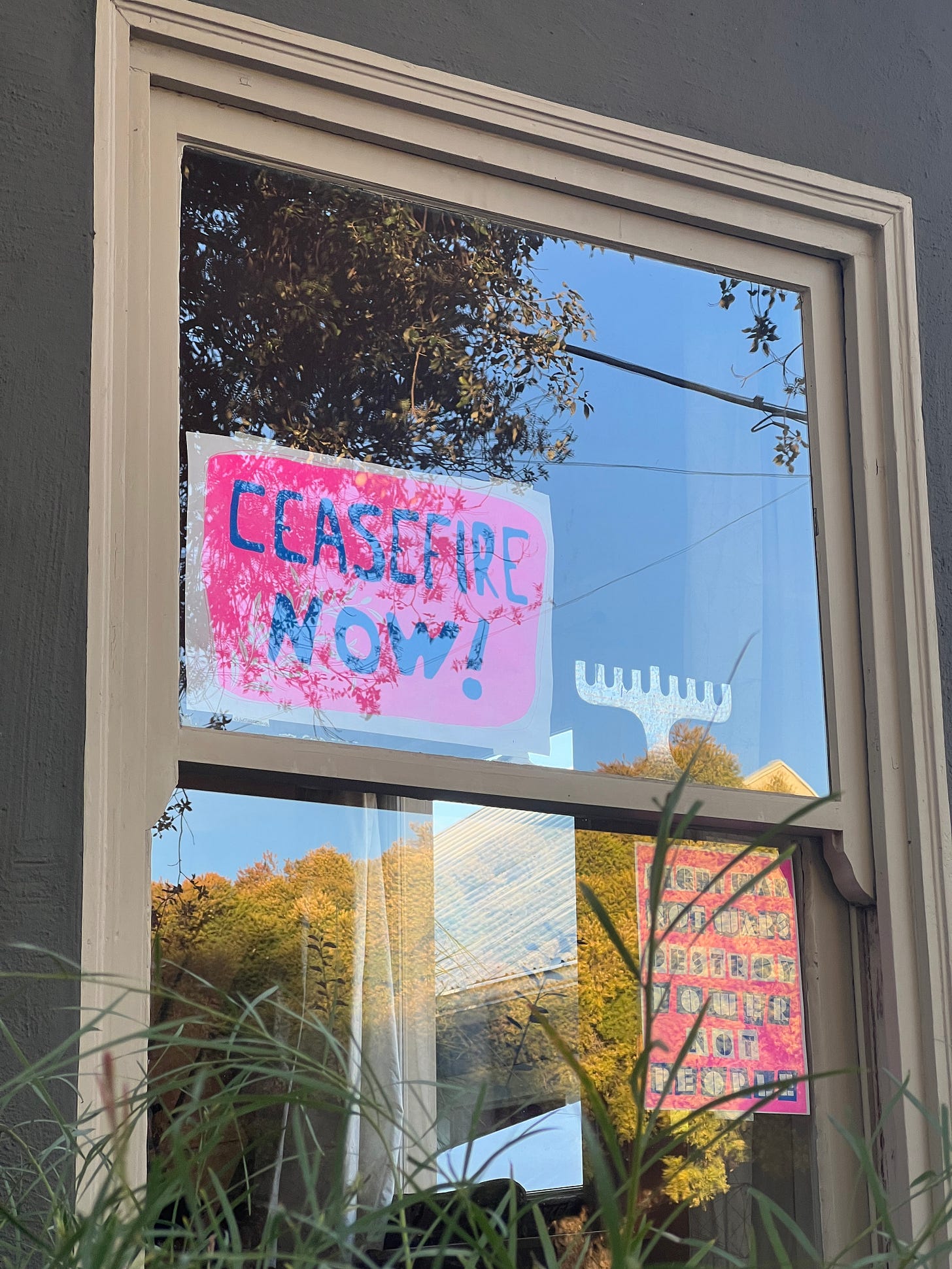

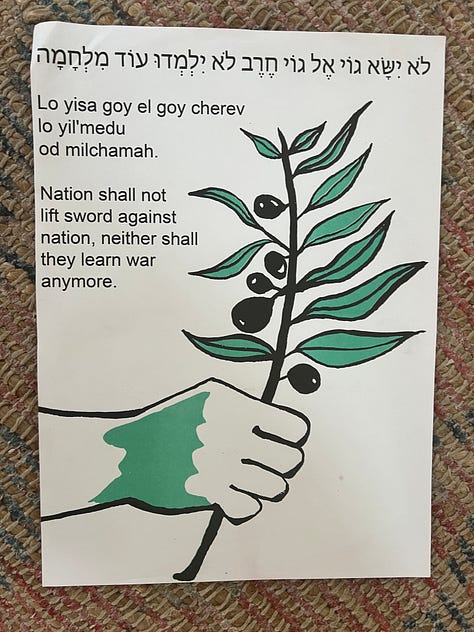

Miriam is also one of the most proud, committed Jews I know. Proud in that she is open and clear about her faith and spiritual heritage. Committed in that she upholds tradition and ritual. And committed in that she is firmly rooted in Judaism’s core principals of justice, community, and liberation for all. Like so, so many, she has been in pain and heartbreak since October 7th. And, like the activist and artist that she is, she’s also been in the activist mode, making the kinds of free posters that she and her wife Lena are known for (like these). Starting on October 8th there have been stacks of free posters on her porch for anyone to come and take. And she’s been mailing posters all over the country.

I asked if she would sit down with me for an actual “interview” and she said OK, and it was kind of a funny thing to do because we communicate all the time but this was different. I wanted to sit and ask questions and listen, to hear her speak to as much of it as she wanted to—her own personal connection to the conflict, how she thinks about posters and the role of the artist in times of war, how she thinks about community and conflict. Miriam loves to say that she’s “shit with words” but that’s not true at all. Miriam doesn’t use a ton of words, but the ones she chooses are thoughtful and real. She says what she means and she means what she says. Yes, she prefers expressing herself visually, through art and posters and papercuts and woodcuts and carvings. But when Miriam speaks you want to listen. And when she listens in return you feel seen.

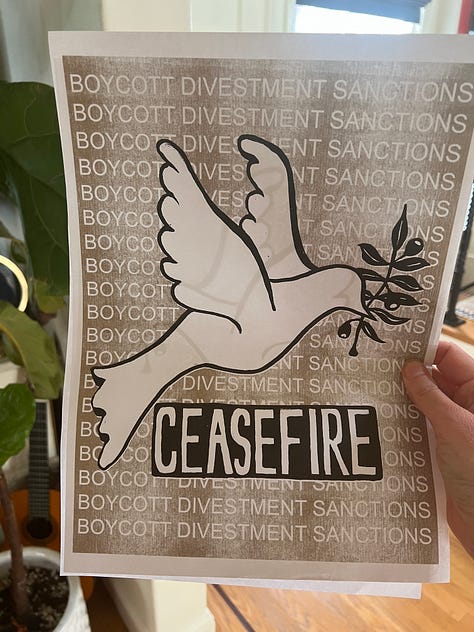

I have learned so much from Miriam over the years that we’ve been in collaboration. About art and process and practice and activism and punk (it should be noted here that Miriam is one of these people who just casually knows every cool person ever but is incredibly chill about it. Ask about the time we ended up backstage with Sleater-Kinney. Or the time she knocked on my hotel room door when we were on book tour in DC and said her friend Ian was coming by in his minivan to give us a tour and an hour lately I was in the basement of the Dischord House, like in the room where Fugazi happened, and yes we took a photo on the porch). Through Miriam I’ve learned about queerness, dyke-ness, anti-capitalism, anti-fascism, anti-Zionism, the BDS movement. It’s not to say that I didn’t know about any of this in my pre-Miriam life, but rather that I’ve gained a much deeper sense of what it can look like to actually embody all of that, all those liberatory ideals, on a day-to-day, lived basis.

I’ve also learned so much about Judaism. I’ve been proximal to and at times immersed in Jewish culture and faith for many decades, via friends, romantic partners, colleagues, neighbors, and many of the social justice activist co-conspirator folks I’ve been lucky to know in the Bay Area. But it’s really through Miriam and her family that I’ve been able to actively participate in a faith tradition that is grounded in an antiracist, feminist, queer vision of peace and dignity and care for all people. And, I am realizing as I write this, it is how I’ve learned what it truly means to be Jewish in this world. What it means to repair and heal the world, the tikkun olam, what it looks like to do a mitzvah, to just be a goddamn mensch. As a white American non-Jew (a shiksa, yes, as a Jewish ex did semi-affectionately call me) raised in a very secular family, it means so much to me to be welcomed to the Shabbat dinners, the Seders, the Hanukah parties, all of it.

I didn’t initially plan to share this conversation with Miriam on the first day of Hanukah—we sat down in her backyard in Berkeley almost two weeks ago, but it’s taken me until today to finally edit it. But it feels appropriate to share this now, in the spirit of this normally celebratory holiday which feels so, so fraught and difficult for so many right now. My heart is truly with all who are feeling that. Hanukah is a celebration of light, and of dedication, so I offer you Miriam Klein Stahl, who is a bright, steady, warm, and very dedicated light to so many. (Miriam would like us to know that Hanukah is “a holiday that’s about resisting assimilation” and also “the invention of guerilla warfare and the murderous Maccabees” and also, of course, “delicious fried foods! It’s latke season!”)

For more wise perspective on Hanukah and its significance right now, I recommend this episode of the new podcast “Jew-ish” from my friend Sera Bonds, and her friend Rabbi Lev, out in Austin, TX

Miriam happens to have COVID right now (she’s OK, just sniffly and feeling pretty poorly) and is isolating in her backyard studio. Tonight she will join her family’s Menorah lighting via Zoom. They’re getting their latkes from Saul’s delicatessen (IYKYK, by which I mean if you know Berkeley you know Saul’s) because Miriam is the latke-maker (I’ve had them, they’re perfect) and no one wants a COVID-y latke. So Miriam, thank you for the light that you are, and get well soon!

I feel like I should add a note here to say that Miriam does not—would not!—speak for all Jews. Not for all progressive Jews, not for all diasporists. But we both speak as people who believe in humanity, in peace, in dignity and liberation and justice for all. And we both deeply wish for an end to the violence, for a true ceasefire, for freedom and liberation for the Palestinian people, for safety and respect for Jews, and goddammit, for all children on this planet to have the chance to play and learn and love and grow up and live a full, free life.

Miriam Klein Stahl is a Bay Area artist, educator and activist and the New York Times-bestselling illustrator of Rad American Women A-Z and Rad Women Worldwide. In addition to her work in printmaking, drawing, sculpture, paper-cut and public art, she is also the co-founder of the Arts and Humanities Academy at Berkeley High School where she’s taught since 1995. As an artist, she follows in a tradition of making socially relevant work, creating portraits of political activists, misfits, radicals and radical movements. As an educator, she has dedicated her teaching practice to address equity through the lens of the arts. Her work has been widely exhibited and reproduced internationally. Stahl is also the co-owner of Pave the Way Skateboards, a queer skateboarding company formed with Los Angeles-based comedian, actor, writer and skateboarder Tara Jepsen. She lives in Berkeley, California with her wife, artist Lena Wolff, and their daughter and dog.

Kate Schatz:

You're someone who has been wrestling deeply with the incredible, complex emotion of all of this, and you're someone who for so long has been firmly rooted in justice and liberation. I want to ask you about art making and posters, and about communication and community. These are all things I think about when I think about you.

But my first question is just: how are you?

Miriam Klein Stahl:

In this very moment? I'm okay. Working a lot and calculating all the things that need to happen between now and winter break.

KS:

Yup. I think everybody's in that zone.

MKS:

And I've just been really sad. I have had some relationships fracture because of radically different viewpoints of what's happening in Israel and Palestine. That's been painful, but more painful is bearing witness to over 10,000 deaths.

KS:

I’m sorry. Does it all feel…surprising to you?

MKS:

I've been involved for a long time in groups that are made up of Jews and Arabs and Palestinians who are working towards a world that is more just for refugees, and for people living in Palestine. A just world for all humans. I’m surprised in a good way, because what's felt like a small community now feels global. And so that part of it is amazing to me, that people are talking about Palestine, all around the world, and identifying with the injustice that Palestinians have been living with for too long. So that part of it feels amazing to me.

And there's a part that feels so difficult. It’s surprising and hard to see people within my community and, you know, one step out of my community, acting as if they're experts on what's happening. Like they've always been in the struggle, and I know for a fact that they've not. There’s this sense of false authority, especially on the internet, that people are demonstrating.

I also think that I’ve let some anti-semitism go unchecked from people that I know. Realizing that is difficult. It’s been right in front of me, though I don’t think it’s intended. I haven’t spoken to it directly because I really don't have the energy for it. And I don't want to be fighting with people that actually really want the same thing that I want. So it’s a choice I’m making to let it go.

On top of that, I’ve had many conversations with Jewish friends who are feeling incredibly disappointed. And really scared. They feel threatened.

KS:

Do you feel that fear as a visible Jewish person?

MKS:

No, I don't feel scared at all. I feel more threatened for being a big ol’ butch dyke in the world! I feel OK. But my daughter has said that it's really hard to be Jewish right now. That is heartbreaking to me.

She feels like there's massive misinformation on social media and that teachers are scared to talk about what’s happening. She and a friend put together a lesson for their high school history class and led a discussion around anti-semitism, and gave a whole history on what has happened on this land for the past couple 1000 years. I’m really proud of her. She spent hours finding sources, they cited everything that they shared. But it all breaks my heart that it’s happening because being Jewish is so difficult for her right now.

KS:

Do you feel that it’s stuff that's been there all along and you haven't been saying anything? Or is it amplified now?

MKS:

I think there's just subtle forms of anti-semitism in America all the time. But it's painful to see it from your people, the ones you've been in struggle with for many years. It just blows my mind to see no compassion for Jews, and for Israelis specifically, that clearly are also suffering. And to just kind of negate that there's been this massive movement for peace in Israel for as long as there's been Israel.

Like, yes, you can hold two things at the same time. You can have compassion for families that have suffered loss within all of those borders. I don't understand why people can't do that.

I have colleagues and friends that have family in Israel, how can I not have compassion for them too? There’s a temple across the street from us, it’s not the temple we attend, but I know the rabbi. His parents live in Israel, his siblings live there. His nephew was killed on October 7. I ran into him while I was walking my dog and I just asked “How are you?” And he's like “The worst thing that could happen to my family has happened already, and I'm trying to see where to go from here.”

And the thing is I know that he and I are not going to agree on what should happen next in that part of the world. We really disagree! But what matters was the human standing across from me, clearly suffering, who lost a beautiful nephew for no good reason. I came home and just felt so much pain for him and his family. I got out my watercolors and I made them a card, and I put it in the mailbox at the Temple because…I don't know what else to do.

KS:

What was on the watercolor card?

MKS:

Just some poppies.

KS:

I think you do know what to do. You went home and you made a gift. That’s what you do, you make. And it means a lot.

MKS:

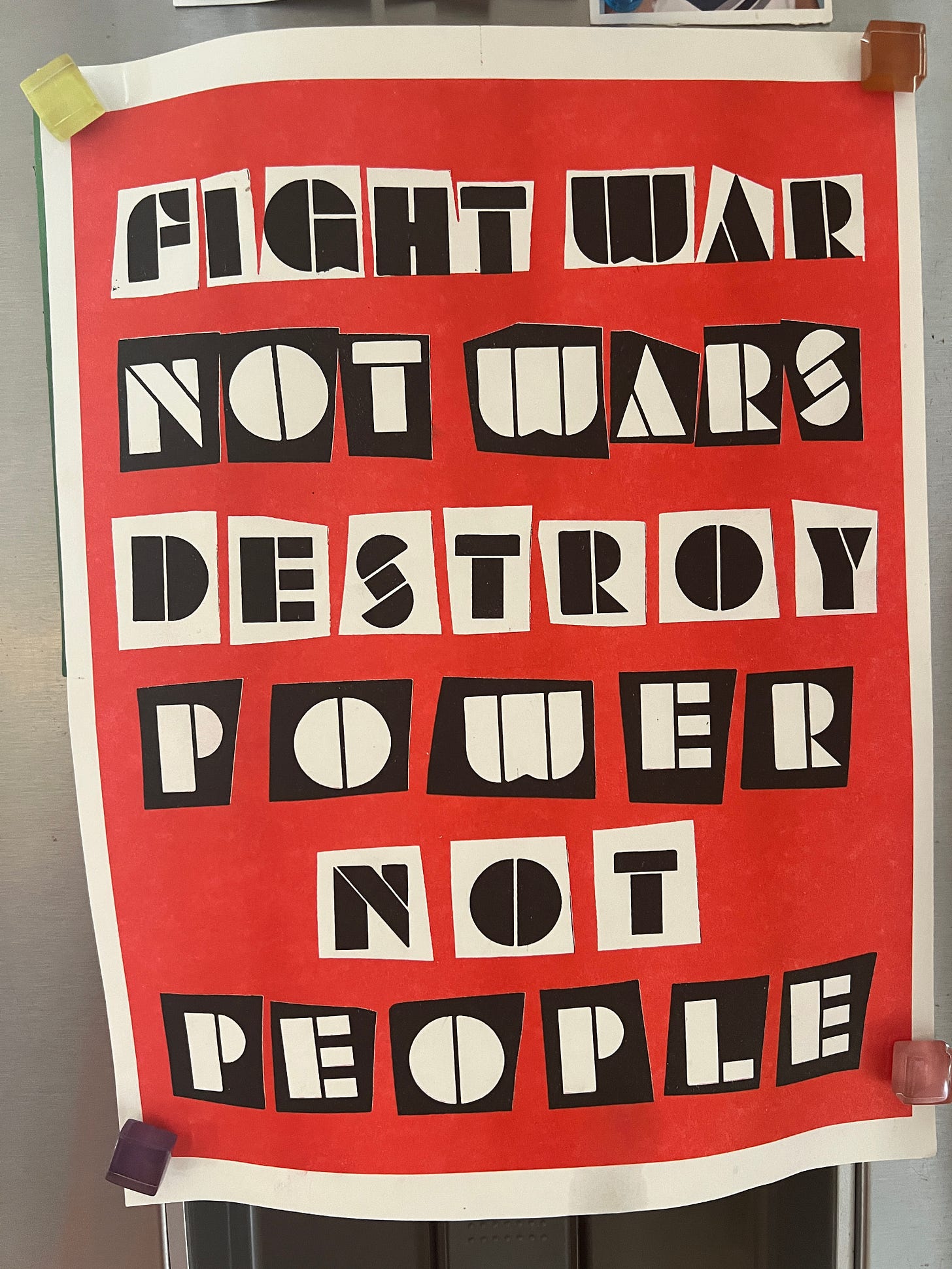

On October 7, I made that poster right away. The one with the Crass lyrics that says “Fight war not wars/ Destroy power not people.” I chose songs lyrics because you know I’m shit with my own words.

KS:

You always say that, and it’s not true.

MKS:

Our whole collaboration has been based on you making words and me making pictures!

KS:

That's why I'm making you talk right now!

MKS:

Well, sometimes other people's words capture perfectly what I'm feeling and I can make them look good and reproduce them quickly. I made 500 of this posters and put them on my porch and also online and said that if people want one they can make a contribution to Middle East Children's Alliance (MECA). Honestly that was such a bad idea because then I ended up having to ship posters to over 100 different addresses, and pay for postage…

KS:

You're ridiculous. I love you.

MKS:

But I thought, you know, that could be my financial contribution to the moment. My wife Lena and I, that's a way that we can contribute to things. We believe in making stuff, especially printed stuff that is accessible and easy to distribute. I would have liked to donate thousands of dollars to MECA but I can't. But I was able to make those posters happen within that first week and through my labor was able to raise thousands for MECA which get aid directly to those in need in Palestine.

KS:

It’s remarkable to me that you made that poster right away. Did that phrase just pop into your head? Did you go back and forth trying to figure out the perfect words? I feel like I would have spent five hours doing that.

MKS:

No, I just immediately made it. Because I knew that there was going to be retaliation and it was going to be fucking awful. And it continues to be every day. Every day I'm lighting a candle and just hoping that a real ceasefire will happen.

And then obviously, I had to make a ceasefire poster. I was very inspired by Jewish Voices for Peace (JVP) actions where people were singing the songs that I grew up singing, so I made that poster also.

The process of making is how I can calm down my entire system. It’s hard to explain it, but it’s like when I’m making something with my hands I have this feeling of calm, and time stops, in a nice way. I feel like my entire body is taking a nice deep breath. Especially once the ideas come already, and I know what I'm doing, and I'm just in the process. Even having to address over 100 envelopes and stuffing them, even that part of direct mail, is helpful to me. Just doing tiny things like that. I mean, I know it's not gonna like, end war, or anything like that, but it's a way that I know how to contribute.

I'll just keep making posters. It’s what I know how to do. And there's just something I really like about being able to give them away for free. Our porch has been a spot for many years now where people can come get free posters.

KS:

Have you experienced any pushback from this round of posters?

MKS:

A lot of people that I don't know on the internet have sent me hate mail. And have stopped following my Instagram or whatever. But I can't be bothered with people that I don't know. What matters more to me is that I've had some hard conversations with people that I do know, where it's hard for them to reconcile that I'm a Diasporist. And not a Zionist.

KS:

Can you explain what a Diasporist is?

MKS:

I live in the diaspora. I am a Jew who will make a home wherever I am, which, right now, is here in Berkeley. And I don't believe that Jews have a right to the land of Israel more than the Bedouins, or Palestinians, Christians or Arabs, or the many people that live there.

I think I am looking for a more nuanced term that speaks to me as a Jew and to my connection to my ancestors, but not an ancestral land. I already call myself an anti-fascist, and I don’t really want all my identities to be linked to being against something that is fucked up. A Diasporist is about being a good steward of the land that I am on. Taking care of the land and the people on it. That’s what boggles my mind about war. Why would you bomb and destroy the land that you love?

KS:

Were you raised otherwise?

MKS:

Oh, yeah. My family is very small, because most of my family were not able to emigrate and therefore were killed in the Holocaust. So I grew up with a very small family, descended from the ones who came to New York during the pogroms in the early 1900s. The rest of their family stayed in Eastern Europe and didn’t survive. Well, there were a couple of survivors that lived with my mom, but very few considering how big the families had been.

So my parents, who are in their 90s, grew up with this as their reality. And they liked the idea that there was a safe place for Jews to be, and to live. It’s very shocking to me, but they have actually changed their tune a little bit lately. Of course, they've long been completely disgusted by the reign of terror of Israel and the right wing zealots that are in power there. But they’ve still held on to that idea that there is this special place. They would contribute to Zionist organizations financially, and though they had no desire to go to Israel, like they never wanted to have the kibbutz life, they’ve always liked knowing that it was there. Because they felt like there may come a day where it's not safe to be here, in America, and there should be a place to go.

KS:

How did you experience all of these histories and ideologies when you were young?

MKS:

I was totally interested in kibbutz life when I was a kid! I had all these communist ideals, and it seemed like a great way to live. I did it, I went to Israel when I was 15, and stayed on one.

KS:

Really? I didn’t know that.

MKS:

Yeah. And it was amazing in so many ways. But it’s also when I witnessed, and began to understand, the injustice of life for Palestinians. Experiencing East Jerusalem, and the discrimination, what it means to live in a place where you don't have representation and the same rights as your neighbors. Going there and seeing that is when I really started to have a change of heart.

KS:

Was it a shock to you?

MKS:

Of course. You don't grow up being told that people were torn from their homes, that their homes were stolen, that they were forced out, that they became refugees. I wasn't told any of that, no way. But that's what happened.

KS:

So you had your own process of figuring that out, and unlearning.

MKS:

For sure. And it's taken many years, decades to unlearn those ideas I was raised with, and I’m constantly kind of reprogramming my brain. I'm a really visual person, so a lot of my unlearning came through art, especially the “Handala” cartoon. Handala is a character who is painted all over Palestine. I saw it when I was there. The artist, Naji al-Ali, was 10 years old in 1948. He and his family became refugees, and when he was older he created this character called Handala that was based on his experience. Handala looks like a kid in a refugee camp: scraggly hair, no shoes, tattered clothing. The image is always the back of him with his hands behind his back. Handala is to remain 10 years old until the Palestinians get the keys back to their homeland.

Seeing that visual when I was young made so sense to me. That, and the visual image of the key. Friends of mine that have gone to Palestine have said that many families still have the keys to the houses that were taken by settlers and so the image of the key represents the hope of one day getting your house back. Getting your land back.

These powerful images have helped me to understand and connect to the feelings of having something taken from you.

KS:

What have your recent conversations with your parents been like?

MKS:

It was really hard at first, but they are speaking out about the brutality of Bibi and his gang of right wing zealots. They still believe in the state of Israel and continue to believe that Jews need a safe place. They also can see that the current Israeli government is horribly corrupt and that the IDF is brutalizing people. And they also view Hamas as a terrorist organization. Because they are! And my parents, they don't want civilians to be killed. They’re rightfully horrified by the numbers, they feel that it does look like a genocide. Because it is. And they also feel like the power needs to be taken away from Hamas. I don't agree with them over how any of this is being done, you know, but at least we can talk about it now.

KS:

I’m so glad to hear that. I know those conversations with them were really tough in the first few weeks after October 7th. I’ve thought about that so much, how it’s been for you to navigate talking with them. You love them so much, but this is a painful place where your beliefs are so different.

MKS:

Thanks. You know, you’re my only non-Jewish friend that reached out to me after October 7th and said, “How is your heart?”

[ED NOTE: I REALLY WANTED TO TAKE THIS PART OUT BECAUSE IT FEELS LIKE UNNECESSARY PRAISE FOR DOING THE MOST BASIC THING BUT I’M LEAVING IT IN TO REMIND YOU TO CHECK ON YOUR FRIENDS]

KS:

Really?

MKS:

Yeah.

KS:

Fuck. I’m sorry to hear that, I really am.

MKS:

It felt really good that you did that. You've made allyship part of your practice in your life. And that's evident. But not very many people do that.

KS:

Well, they should.

MKS:

They really should.

KS:

In the midst of so much overwhelm we do really forget how much these small human moments can mean. To just send someone a message or a text and say “Hey, I’m thinking of you, I love you.” Or “I see how difficult this is for you. I'm so sorry.” Moments of actual connection mean everything when we’re feeling so profoundly disconnected.

MKS:

It’s all we have. Being in community, breaking bread with people, being with people in real life. I’ve gotten off the internet as well. I'm on it a lot less these days. It's good to connect, but it's also good to step back.

I also spend a lot of my time in my teaching practice. So I’ve had to figure out how to bring this all into my classroom in some way. I'm no historian, I can't teach a full history of a place with such a long complex history. So I rely on art. I showed some work from a Palestinian artist, I showed an Israeli artist. Really cool stuff from both. We watched video clips of both artists talking about their practices, and what the students saw was also the stark difference of accessibility. This Israeli artist had come to Los Angeles for a big exhibition, while this Palestinian artist can't leave where they live. They can't get the paint they need, so they figured out how to make their own paint. And there's no art market for the Palestinian artist. The students could see that, they could connect with that. They’re living in the Bay Area, they know what income inequality looks like. They see what people do and do not have access to, and they could draw lines between injustices here and in that region.

KS:

Speaking of being in community, I know you’re been going to services at your Temple. How has that been feeling lately?

MKS:

It’s completely comforting, because it's a synagogue that I am aligned with politically and spiritually. Those are my people. I find great comfort in it. We went to Shabbat services on the first Friday after October 7. There’s just something so comforting to me about singing the songs that my ancestors have sung for 1000s of years. It's almost that feeling of artmaking that calms my nervous system. Being part of this lineage and knowing that part of my culture is to speak out about injustice, and that we don't have to all agree. I mean, that’s such a big part of it. It really, really is. It's been hard for me to accept people that are digging their feet in to Zionism at this point, but I am also trying to be compassionate while I disagree.

At this point in my life, being in my 50s, I've surrounded myself with a community that I'm pretty aligned with. 98% of the Jews that I know are diasporists. I’m really trying to get that word in there.

KS:

You’re trying to make diasporist happen! I appreciate it. Is it a word that a lot of people are using?

MKS:

I want them to! I mean, it makes sense. We are a people in the diaspora. We've been moving around for 1000s of years.

I happen to be here now, but I might not always be here and I don't feel a claim to this land. I feel lucky to be on it. I honor the Ohlone people as much as I can, including by paying Shuumi, my land tax. I love living here, but this is not “my” land. And I could just as well live somewhere else. Because I'm a Diasporist!