Hi.

This week’s newsletter was going to be about abortion. But I switched gears and now it’s about death.

Well, not death yet. The dying process. Hospice. Because I’m in Texas right now, have been here since Friday, with Lauren, my wife-to-be, and her sister. And most importantly: I’m here with their mother, Darlene, who is dying.

They are caring for her. And I am helping care for them. And today I realized that I think I need to write about it. With Lauren’s permission, I’m sharing a little bit of it here, with you. So please, if reading about end-of-life doesn’t feel right for you, or isn’t what you signed up for when you clicked ‘subscribe’, skip this one. It’s really ok. (Also: I highly recommend subscribing to Jessica Valenti’s newsletter Abortion, Every Day.)

January 22nd was the 50th anniversary of the Roe vs. Wade decision—a shitty anniversary, but a marker nonetheless—and I was set to profile some great folks working in reproductive justice: a person running an abortion access fund in West Texas, a law professor and anthropologist who specializes in the intersection of race, law, and reproductive justice, and an artist making large-scale installations of abortion pills. It’s nice to publish things that coincide with specific dates and holidays, but I know that this work matters and is needed every single day, and I will get to that coverage soon.

The right to bodily autotomy, quality healthcare, and dignity in the choices we can make about our bodies and futures still feels incredibly relevant—just in a different way. There’s the dignity of how we bring people into this world; the dignity we afford ourselves and each other as we live out these lives; and the dignity of how we go out. That’s where we’re at right now, in this house: Darlene wants to die at home. And that’s what we’re helping her do. Giving her care, comfort, and dignity, with as much peace as we and the wonders of modern pain medication can provide.

She is dying of cancer, a recurrence of the endometrial cancer that almost killed her 12 years ago, before I got the pleasure of knowing her. But she beat the odds and survived, and Lauren had her son soon after her recovery, and Darlene got some incredible years as the most enthusiastic grandma ever. The cancer came back a year and a half ago, the bastard, and it’s been…horrible. She lives alone, had just moved into a brand-new just-built house in a massive “active senior” retirement community about 45 minutes north of Austin. We have been back and forth, OAK—>AUS on good ol’ Southwest, so many times.

This time right now, this passing—it’s not a surprise or a shock. We’ve spent so much of the past year navigating the anticipatory grief, the knowledge she won’t be at our wedding, all of it. It’s gutting, but it will be a relief. She’s been in so much pain. So many surgeries and medications and attempts to fix it and in the end, two weeks ago, she was ready to say the word hospice. And her doctor said Yes, I think it’s time. And the next day the hospice people came to evaluate her. And the next morning the hospice nurse called Lauren and said “You should come now.” And so she was on her way, as was her sister, and then I came too.

I’ve never been proximate to death like this. I’ve never partaken in or witnessed caregiving like this. It is a wild, deep honor—that’s really all I can say about it right now, while still in the shifting, roiling, surreal midst of it all. I see my role here as kind of emotional- support-pet/errand runner/quiet back-up support. Trying to stay low and quiet and out of the way, stepping in when it seems helpful, but also stepping back, out of the room during particularly tender or intimate or complicated times (unless my physical help is needed).

(Though right now I’m snacking on my favorite chips that I found in a “Natural Food Store” and I just looked up and Lauren and her sister are laughing and staring at me from the other end of the house. I’m crunching so loud! Oh my god I’m such a jerk. So much for being all quiet and non-intrusive, I’m just over here chomping on the loudest chips ever invented.)

The house is so quiet so when I leave the house to run errands in the rental car, to pick up the fentanyl patches and morphine from the pharmacy, I turn the music up loud. I turn right at the intersection of Ronald Reagan Parkway and Rattlesnake Rd (those are actually the street names), and I sing along to “Farewell Transmission” by Songs: Ohia (or technically Magnolia Electric Co, I guess). And I cry when Jason Molina (RIP) sings “Real truth about it it/no one gets it right/Real truth about it is/We all just have to try.”

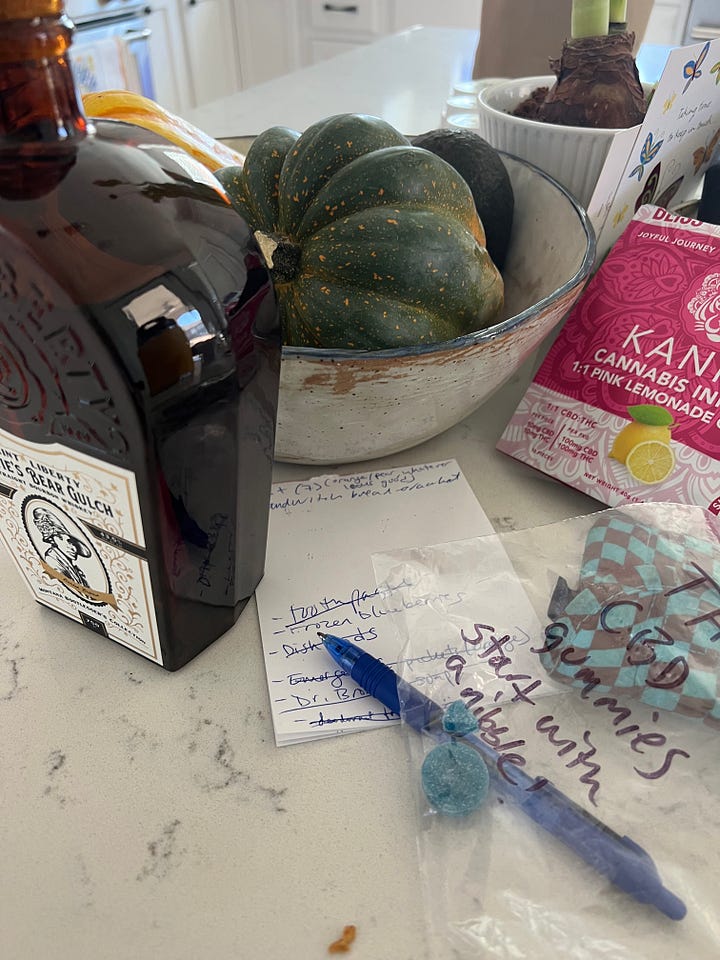

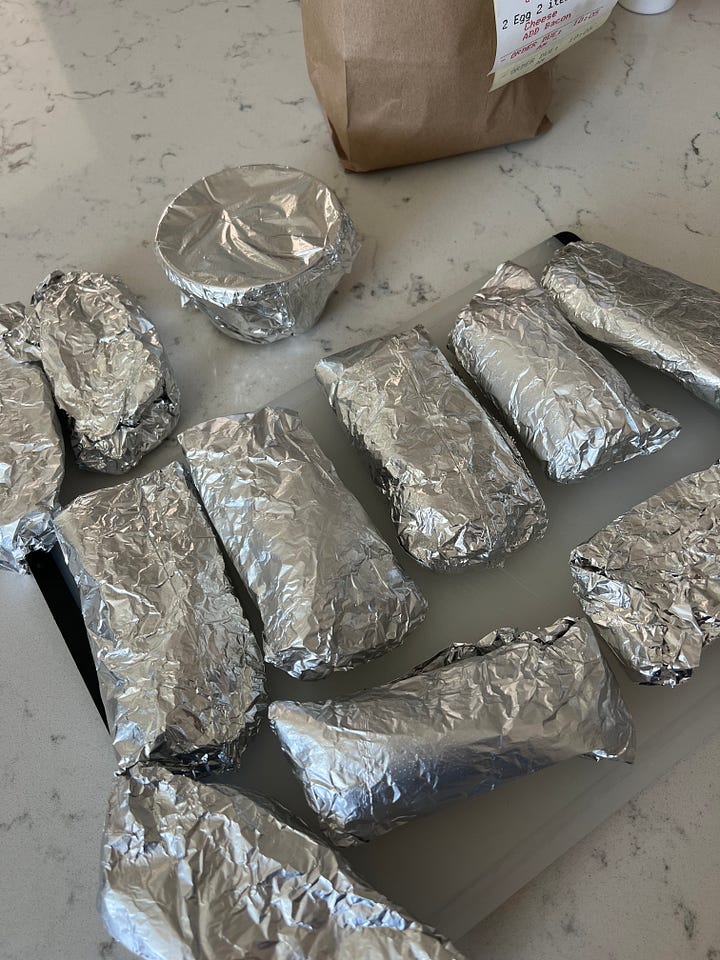

I love what these two sisters are doing so, so much, because it is the most profound act of love I’ve ever witnessed. I joke that their family’s love language is logistics, and I’m only kind of kidding. It’s attending to details, it’s acts of service, it’s a deep attention to each other. Lauren went to nursing school and while she doesn’t work as a nurse now she’s unbelievably good at it. Her sister reminds us she is “not a medical professional” but she’s incredible, too: consistent, thorough, gentle yet firm. They give support and care and love and morphine and oxy and chapstick and sips of bubbly water and bedding changes and bites of Jell-o and whispered words of comfort and assurance. They’re stern when needed. They keep her warm and clean, they tell her when the straw is going to touch her lips. Last week, when she was more active and lucid, they were giving ice cream and weed gummies and they were taking notes and completing tasks because Darlene is the most organized person you’ve ever met in your life and this is a very thorough death with everything accounted for. The T’s are crossed, the I’s are dotted, the Pottery Barn credit card has been closed.

Each day is different, because each day is closer to the end. I’m learning so much about it all: about hospice care and how it works, especially when an in-home death is preferred. I’ve learned about Dame Cicily Saunders, the British nurse who essentially invented modern hospice care and changed the way that Western medicine understands palliative care. (Her most famous quote: “You matter because you are you, and you matter to the last moment of your life.”) I’m learning about the end stages of life, or rather, the stages of dying. How the body shuts itself down, how hearing is the last sense to go. What to look for: slowed respiration, low blood pressure, lack of appetite, so much sleeping.

She’s had some lucid moments over the past few days, including one surprisingly hour-long interlude where she was alert and funny and we all laughed when she referred to Lauren as Nurse Ratchett. She complimented my ponytail braids, and she admired the cartoon skateboard ramps on Lauren’s oversized Spitfire hoodie. But yesterday and today feel very different. The lucid conversation times belong to a now-passed phase. No longer able to get out of bed. No longer eating. No longer talking, except soft one-word answers to questions about pain control and physical comfort.

(Lauren just came into the room and opened one of the many cute decorative boxes in here. She’s looking for a gun because last week Darlene informed her there’s a gun! What? Mom, you have a gun?! Where?! It is Texas, after all. It was a gift from her ex-husband. And apparently it’s stashed away somewhere but she can’t really remember?! Lauren looks through the box, gingerly. Nope, no gun. Just more picture frames. A gun? Shit.)

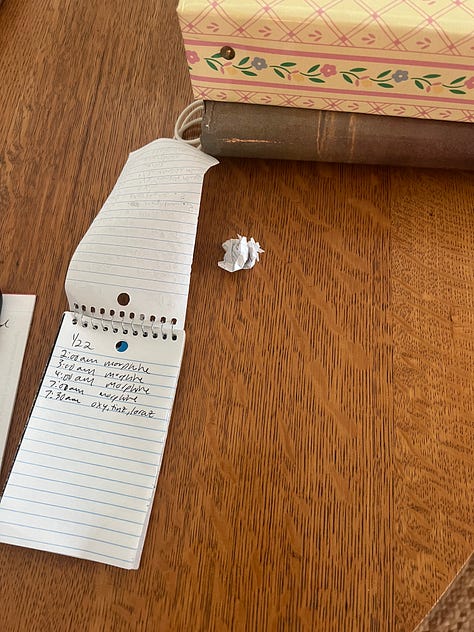

Lauren has been writing down some of the nonsensical phrases she began uttering, once the morphine was flowing. Like when she looked at Lauren knowingly and said “Slow…like aviation.” Lauren said what mom? And she repeated it, with clarity but no further explanation. It feels like a perfect phrase. At one point she woke in the night and wrote FLEX FLEX FLEX! on a piece of paper. I love that too.

When I got here I asked the sisters if they’re ok with me documenting some of this time, and they said yes, so I’ve trying to get some photos, capture the lucid moments on video and voice memo. I know this time will all be a kind of blur and I want there to be evidence of her voice, what it all looked and sounded like. Photos of them in the room with her, yes, but also other details: the shadow that the bouquet of flowers casts on the wall above her bed. The blue and white ceramic bowl in the fridge, stocked with tiny plastic syringes preloaded with morphine doses. The unbelievably vaginal amaryllis that’s been swelling and blooming and finally opening. The embroidery that my daughter made for Darlene, with the ‘N’ for Nonni which is what the kids call her, and her beloved California poppy. The kitchen counter tableau of pills, THC gummies, hospice literature, whiskey, and the remnants of the breakfast tacos that were kindly DoorDashed to the house for us. The bright red cardinal who keeps coming to visit the bird feeder outside the kitchen window. The stuffed animals I bought for the sisters from the cheesy Valentines Day section at the grocery store: a cat for Ali who’s really missing her own kitty, and a bear dressed as a bee for Lauren (“It’s NOT Busy Bee! It’s a BEAR dressed as a BEE!” IYKYK).

We kind of just stand around the kitchen a lot. We shuffle around the house, too, we do laundry, dishes, I try to make them eat. I give a lot of hugs, say things like how are you feeling so far today and you’re doing such an incredible job and you are amazing and this fucking SUCKS, I am so so sorry. We sit and look at laptops, we take walks around the identical planned-community neighborhoods and the “nature trails” where we see lots of white-tailed deer hopping through the scrubby Texas trees. We chat about the weather, the birds in the yard. We check on her constantly, the way we checked on the babies when they were new and napping—still breathing! We hear when she shifts and moans, we go in to the room to get her comfortable again. I relocated the Ring security camera and set up everyone’s phones so we can watch her. A live feed—until it is not, I guess. Is that an OK joke? Hard to tell sometimes. Anyway. We sit and whisper-talk, we look through old photos, we remember to shower and change into the other pair of sweats we shoved in the suitcase. We reply to texts and read books and have hushed phonecalls. The sisters huddle together to discuss schedules, logistics, all the many details of a death process. We look at each other in disbelief and mouth what the fuck a lot.

The thing is: it’s so much more than what I’m describing here. It’s all so scary and exhausting and much of it feels too intimate, private, primal and raw to fully articulate. Many of the details aren’t mine to share. There have been traumatic moments, scary falls, firefighters here at 5am to safely get her off the floor. The sisters have been up for hours at night trying to soothe and calm. Last night we finally got extended release morphine—we all slept through the night for the first time in a week. This is all such a profound gift but it’s far from perfect, it’s far from words like “right” and “ideal.” So little goes according to plan. Death is the ultimate plan-fucker! It’s hard and scary and sometimes gross and also, somehow, so beautiful.

The world outside this house in central Texas floats on the periphery—I know about Monterey Park, and now Half Moon Bay, Lunar New Year joy turned to American tragedies. Shooting in Oakland right by my daughter’s school. I know there were marches across the country, and something something classified documents. The kids are with their dads and they send videos of the basketball game, baseballs tryouts. My son lost a tooth and he FaceTimed me to show me. It’s all…out there. The events of the world exist right now like the spirits or spots or shapes that, at least a few days ago, were sometimes passing through Darlene’s line of vision. She would wave her arm slowly, arcing as if to touch the spirits we couldn’t see. Is that a cat? Is someone here?

Who’s to say there’s not a cat here? Who’s to say the room isn’t filled with friends and friendly strangers? An apparitional welcoming committee? I’m not a religious person, wasn’t raised with any distinct spiritual or cultural ideas around afterlife and what happens beyond our time on this particular plane. But I’m 10000% open to the not-knowing, and to all the possibilities. Is this room actually filled with cats?! What if it is? Is there someone sitting right there, talking to her? Is there a group of people with lanterns and informational pamphlets, waiting to show her the way? Why not?

Last night, after the sisters went to sleep, I stayed up until I was sure Darlene was settled. I sat on the floor of her room and whisper-read a bunch of Mary Oliver poems. Because, duh, Mary Oliver is perfect. I really don’t think she could hear me but I like to think that the words flew around in the same air as all those friendly spirits.

I listened to Alua Arthur, an incredible death doula, on a recent episode of We Can Do Hard Things (a podcast I listen to frequently, and have complicated feelings about frequently. But I continue to listen.) Alua is the founder of Going With Grace, and among the many profound insights she shares on that episode is around how limited we are with our versions of post-death narratives. Literally no one knows what happens after we die, and that means that anything is possible. And culturally we’ve chosen so poorly! Eternal damnation? Hell? Angels in clouds with harps?! This is so uncreative. We can do so much better! What is the afterlife is just a continuous glitter wave of the best feelings you’ve ever felt, all your favorite tastes and smells and sounds? Everything everywhere, all at once. (Give that movie all the Oscars, please.)

I leave here tomorrow, returning to the world of kids and pets and sports and loose teeth (ew, the worst, I hate loose teeth). Lauren’s sister leaves on Friday, returning to Kentucky to take care of her cat, some work, to see her husband. She’ll return. Lauren is staying. We’ve lined up dear friends from Austin to come stay with her, bring more breakfast tacos and wine. She won’t come home until Darlene has passed, and I will fly back here and then we’ll return to California together with the remains in a bag that she’ll carry on the flight. The man from the mortuary said on the phone, in his thick Texas accent: “Now ma’am, I’d like to respectfully suggest that you don’t check your mother. Please carry her on.”

It’s good advice.

I’m not sure how to end this, in part, I suppose, because I don’t know how this ends. Maybe I’ll ask you for advice, those of you who’ve been through it? What brought you peace? What helped you grieve? What did you wish you’d known? I’m happy to hear it all, and to pass on words of wisdom and care to these two incredible sisters.

You now what? Let’s end with Mary Oliver. Because, again, duh.

from “To Begin With, the Sweet Grass”

3.

The witchery of living

is my whole conversation

with you, my darlings

All I can tell you is what I know.

Look, and look again.

This world is not just a little thrill for the eyes.

It’s more than bones.

It’s more than the delicate wrist with its personal pulse.

It’s more than the beating of the single heart.

It’s praising.

It’s giving until the giving feels like receiving.

You have a life—just imagine that!

You have this day, and maybe another, and maybe

still another.

**Darlene Teresa Pariani passed peacefully, at home, on the night of Thursday January 26th, 2023, about 12 hours after I published this piece.**

Kate, my sister passed in October while in hospice. She suffered with extreme MS disability for some years. She was in a hospice care center. I went out to give my nieces a short break and stayed in her room. She unexpectedly passed the next morning while I was there. To be of service to her and them in her passing was a humbling and deeply connecting experience. Reading this was very touching. I send my love and hope that she has a peaceful passing that brings the same comfort to your partner and the whole family ❤️

❤️